Has anybody ever told you they’re a visual learner? Statements like these are common. Indeed, the idea of tailoring instruction to specific learning styles is both appealing and hotly debated.

This personalised approach holds the promise of increased engagement and deeper understanding for all students.

But a plot twist emerges: the very foundation of learning styles is contested. Despite most of the research telling us otherwise, the notion that we all learn best in different ways remains popular.

But popular notions aren’t always true. You can’t see the Great Wall of China from space. Penguins don’t mate for life. And our self-defined learning style has not been shown to have any real impact on educational outcomes.

In other words, learning styles are a myth. You can have a learning preference, but catering to it won’t necessarily result in better learning experiences.

Frustration often arises because many practitioners choose to ignore the mounting evidence against learning styles. Others remain blissfully unaware of it. As a result, our understanding of how we learn has failed to evolve over time.

As the saying goes, when the legend becomes fact, print the legend. But if we can stop pretending that learning styles make any real difference, then we can start reapplying our focus to evidence-based approaches that generate real impact.

In this article, we’ll take a look at what the research tells us about learning styles. But first, let’s start with a definition.

What Are Learning Styles?

An individual’s learning style refers to how they believe they best absorb, process and retain information. For example, if you were learning how to change a tyre, what approach would you take?

- Visual learners would likely find a ‘How to’ video on YouTube.

- Aural learners may request advice from an expert.

- Kinesthetic (or tactile) learners may attempt to learn through trial and error.

- And verbal learners (those who prefer the written word) may refer to their car’s manual.

Some people believe they have a dominant learning style. Others rely on a mix of different styles to achieve learning nirvana. You may also be able to strengthen your ability to benefit from different learning styles with consistent practice.

Either way, most learning stylists believe that optimal learning happens when we appeal to learners’ beliefs about how they learn best.

Where Did Learning Styles Come From?

The world of instruction is overrun with competing models of learning styles. In fact, as far back as 334 BC, Greek philosopher Aristotle noted that children possess individual talents and learning preferences.

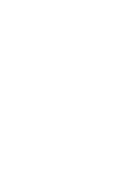

However, perhaps the best place to start is with David Kolb, who in turn built on John Dewey’s progressive education philosophy. In 1984, Kolb introduced his well-renowned experiential learning cycle. According to this model, the ideal learning process engages four different modes:

- Concrete Experience: Learning through hands-on activities and direct experiences.

- Reflective Observation: Reflecting on and analysing those experiences.

- Abstract Conceptualisation: Developing theories and concepts based on those reflections.

- Active Experimentation: Applying the new concepts and theories to new situations.

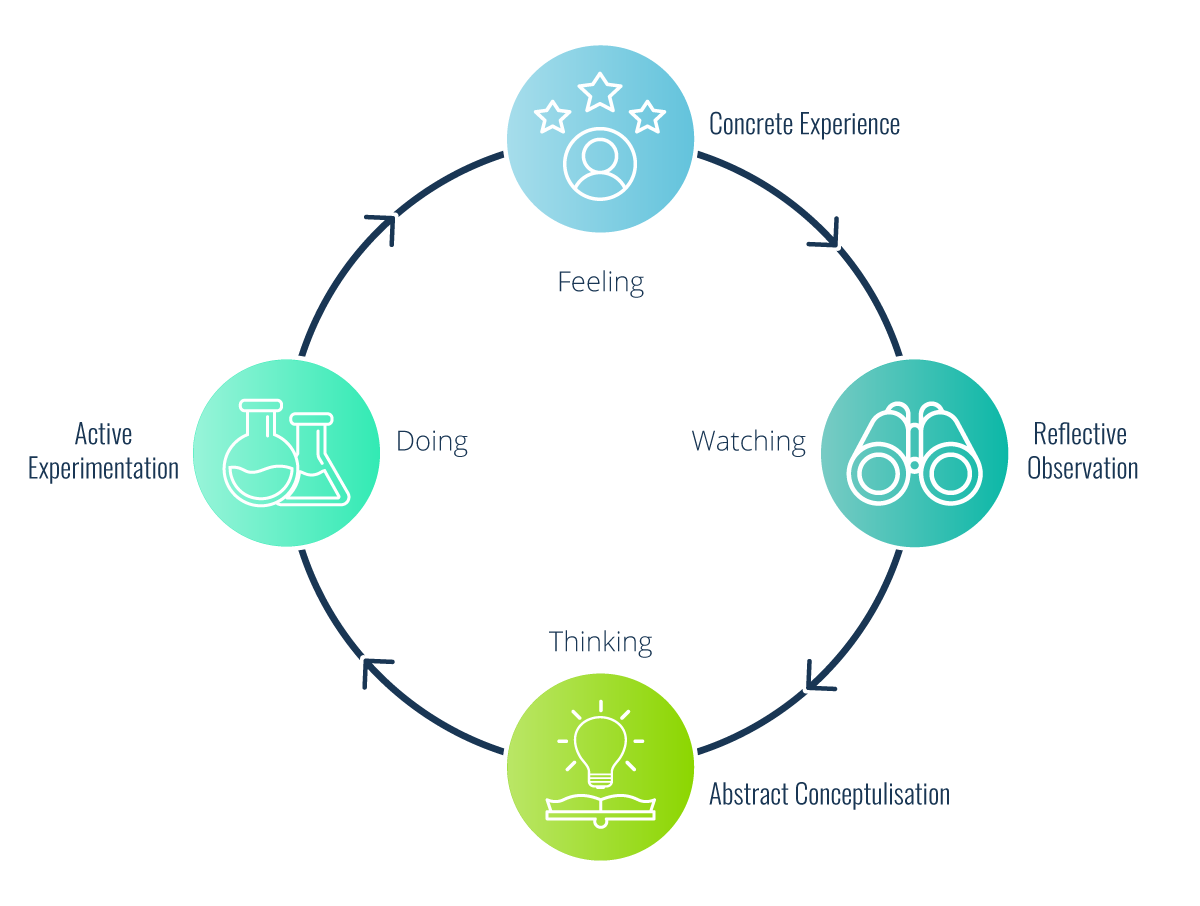

Combining these modes in response to situational contexts results in good learning experiences. Kolb also noted that learners tend to prefer certain combinations of these modes. In other words, they develop a preference for a certain learning style. For example:

- Divergers: These learners prefer to combine Concrete Experience with Reflective Observation and excel at gathering information.

- Assimilators: These learners prefer to combine Abstract Conceptualisation with Reflective Observation and tend to be analytical.

- Convergers: These learners prefer to combine Active Experimentation with Abstract Conceptualisation and focus on problem-solving and decision-making.

- Accommodators: These learners prefer to combine Concrete Experience with Active Experimentation and thrive on hands-on experiences.

Kolb’s model is still widely accepted and supported, but the idea that these preferences affect learning outcomes is disputed.

VARKing Up The Wrong Tree

However, this idea never truly went away. It certainly seemed to inform Neil Fleming’s thinking in the 1980s. During this time, he was working as an inspector in the New Zealand school system.

Fleming saw that some teachers found it easy to get through to students whilst others struggled. This led him to create a learning preference questionnaire. This questionnaire categorised students based on their favoured learning style.

By 1987, Fleming had leveraged this data to create the VARK model and inventory. There are over 70 different learning style classification systems, but this one is the star performer. It’s an acronym which stands for:

- Visual: These learners have a preference for seeing. They love visual aids like graphs, charts, diagrams, infographics and so on.

- Aural: These learners have a preference for listening. They thrive on lectures, discussions, podcasts and similar audio-based experiences.

- Read / Write: These learners have a preference for the written word. They do best by reading and writing up their notes.

- Kinesthetic: These learners prefer to learn through experience. They will favour project-based and scenario-based learning.

The VARK model suggests that learners have preferences for how they consume information and that these preferences help to determine learning outcomes. In other words, it neatly squeezes learners into specific categories.

If this approach feels a little simplistic to you, then you’re not alone. It’s almost like a ‘Which Simpsons Character Are You?‘ BuzzFeed quiz.

This differs from something like Howard Gardner’s theory of Multiple Intelligences. After all, Gardner argues that his eight intelligences represent mental capacities, while learning styles describe preferred approaches. One doesn’t necessarily dictate the other.

Honey & Mumford Learning Styles

Let’s explore one other popular framework used to understand learning styles. In 1986, Peter Honey and Alan Mumford identified four distinct preferences that people use while learning. They are as follows:

- Activist (Doers): These learners prefer hands-on experiences, challenges and problem-solving activities. They’re great at brainstorming exercises, role-playing scenarios, and simulations.

- Reflector (Thinkers): Reflective learners enjoy observing, analysing and mulling over new information. As such, they prefer lectures, discussions and case studies that let them consider material from different perspectives.

- Theorist (Logicians): Theorists crave logic, structure, clear definitions and explanations. They learn best through lectures, detailed demonstrations, and through testing out their hypotheses.

- Pragmatist (Appliers): These learners are all about practicality and relevance. They focus on applying knowledge to solve real-world problems. As a result, they benefit from case studies, problem-solving exercises and project work.

The Honey & Mumford model, like other learning style models, is not a rigid categorisation system. Most learners mix and match these preferences as appropriate. Indeed, their dominant learning style is likely to depend on the subject matter or learning context.

Why Did Learning Styles Catch On?

This categorisation spread like wildfire through all discourse about effective learning. It’s not hard to see why. The theory has huge appeal, despite the lack of supporting evidence. For some, it even feels intuitively true.

Learning styles offer a seemingly clear-cut framework for understanding individual learning differences. This simplicity can be appealing, especially when contrasted the complexities of human cognition.

After all, we all like to believe we’re special in some way and we’re all striving to understand ourselves better. The existence of learning styles would suggest that we’re uniquely wired to absorb information in certain ways. As a result, for somebody to effectively communicate an idea with you, they need to do so on your terms.

For example, Donald Trump relies on oral intelligence briefings because reading ‘is not [his] preferred style of learning’. What’s more, this 2016 blog categorises Albert Einstein, Leonardo Da Vinci and Pablo Picasso as ‘famous visual learners’. Would they have agreed with this distinction?

What’s The Issue With Learning Styles?

We should take care not to confuse learning styles with personalisation. Tailoring learning experiences and providing individualised education is inherently valuable. But, this does not mean we should slavishly appeal to our learners’ specific preferences.

Unfortunately, it’s not just those outside the world of learning who help to exacerbate the myth of learning styles. A 2021 study by Professor Phil Newton found that almost 90% of educators believe in the efficacy of learning styles. Yikes.

Furthermore, researcher William Furey notes that ‘government-distributed test preparations on high-stakes certification exams include the debunked theory of learning styles’ across 29 states.

As Professor Newton notes: ‘This apparent widespread belief in an ineffective teaching method that is also potentially harmful has caused concern among the education community’. Clearly, there is an issue here that needs to be addressed and overcome. Let’s hear more from the dissenters.

What Does The Evidence Say About Learning Styles?

The main issue with learning styles is the lack of evidence to support them. They eat up a lot of focus, without providing any real benefit. Take a look at the studies below:

- The Educational Endowment Foundation in the UK concluded that learning styles offer ‘low impact for very low cost, based on limited evidence’.

- A recent study called ‘Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence’ concluded, ‘Learning styles theories have not panned out, and it is our responsibility to ensure that students know that’.

- A 2014 paper from the Journal of Educational Psychology suggests, ‘Educators may actually be doing a disservice to auditory learners by continually accommodating their auditory learning style, rather than focusing on strengthening their visual word skills’.

- This 2023 study notes that thinking in terms of learning styles places artificial limitations on parents’ and teachers’ understanding of children’s academic potential.

There’s also evidence that suggests that we are bad at determining our own preferred style of learning. Research conducted by Gregory Krätzig and Katherine Arbuthnott contrasted learners’ own perception of their learning style against the results of a learning style questionnaire. There was less than 50% correlation. Our perception does not always align with objective reality.

Why Limit Your Learning?

These studies only begin to scratch the surface. Even Neil Fleming urged caution about reading too much into the VARK model. Back in 2006, he said: “I sometimes believe that students and teachers invest more belief in VARK than it warrants. You can like something, but be good at it or not good at it.”

In other words, having a preference tells us nothing about the quality of any associated acts. You can enjoy football without having Lionel Messi-esque levels of talent. In the same way, you can like visual learning without being particularly adept at it.

As educational psychologist Paul Kirschner puts it: ‘while most people prefer sweet, salty, and/or fatty foods, I think we can all agree that this is not the most effective diet to follow’. But that’s not the only problem with learning styles. Here are the key issues as we see them:

- Limited Evidence: As we’ve seen, most research fails to draw a direct line between learning styles and improved outcomes. While some studies suggest a connection between learning preferences and information processing, there’s a lack of strong evidence that you’ll see any real impact from this.

- Oversimplification: Learning styles categorise learners into distinct groups, which may not accurately reflect reality. After all, most people demonstrate a variety of learning preferences depending on the subject matter at hand, or the situation itself.

- Potential for Stereotyping: This rigid categorisation can also lead to stereotyping learners and limiting their potential. For example, assuming an auditory learner can’t grasp complex concepts through visual means could hinder their learning journey.

- Style Over Substance: Focusing on learning styles can be a distraction that overshadows the importance of effective learning strategies. We already know that actively engaging with material through spaced repetition, retrieval practice and self-explanation works. The same can’t be said for learning styles.

- Implementation Challenges: Let’s not forget, implementing learning styles is challenging, especially with larger groups of learners. After all, tailoring instruction to a wide range of learning styles can be time-consuming and difficult to manage. You’ll want to make sure you’re spending this time wisely.

How to Use Learning Styles (Properly)

Despite these issues, there’s no need to completely discard the idea of learning styles. They’re still a useful tool for learning professionals, provided they are used in the right way. Here are our suggestions:

- Encourage Variety: Even if you don’t actively cater to each individual learning style, this framework still encourages you to explore different ways of presenting information. Where possible, you should consider incorporating visuals, kinesthetic activities and a variety of learning materials to cater to diverse groups of learners.

- Increase Engagement: Providing a variety of learning experiences can help to create a more engaging and stimulating learning environment for a wider range of students. This could be the spark you need to encourage activity within your learning system.

- Promote Awareness: Discussing learning styles helps learners to reflect on their preferred ways of taking in information. This self-awareness can empower your audience to explore different learning strategies and find new approaches that work for them. This is especially true if your learners understand that their preferences won’t impact their outcomes.

Final Word

Learning isn’t easy. It takes time and effort. It can be a painful process. As such, it’s natural for us to want to ensure that this time is being used effectively.

This can lead to us forming preferences for certain ways of learning that we perceive to be effective. However, we should not make the mistake of believing that our preferences determine the quality of our educational output.

The great majority of research into learning styles suggests that they have a negligible impact on our capacity for learning. Exacerbating the myth only obscures the discourse and prevents us from focusing on other learning approaches that have proven to be effective.

Good learning is learning that is free of limitation. It requires an open mind and a creative approach. In order to move forward as a discipline, learning professionals need to shift their focus from learning styles, embrace new approaches and adopt research-backed learning theories as part of their instructional arsenal.

If we can achieve this collectively, then learning styles will soon become a thing of the past.

Thanks for reading. Whilst there’s little evidence to support learning styles, the same can’t be said for the theories and models we’ve collected in our bumper guidebook, ‘The Learning Theories & Models You Need to Know‘. Download it now!