Do learners perform better when their material aligns with their preferred learning styles? This question lies at the core of the VARK model, a widely recognised framework for understanding learning preferences.

The idea that learners perform best when instructional methods align with their self-reported learning styles gained traction in the 1970s and 80s. However, while the concept remains influential, the science behind it is hotly debated.

Whilst the VARK model’s effectiveness in directly boosting achievement is contested, it can still offer valuable insights for learning professionals. This is especially true if you understand the limitations of the model.

Indeed, its creator Neil Fleming suggested that VARK was a ‘catalyst for reflection’, not a rigid set of categories. As Fleming himself puts it, “students and teachers need a starting place for thinking about, and understanding, how they learn.”

This article explores the ongoing debate around learning styles, the strengths and weaknesses of the VARK model, and its relevance to learning professionals. Visual, auditory, read/write, and kinesthetic learners — you’re all welcome to proceed!

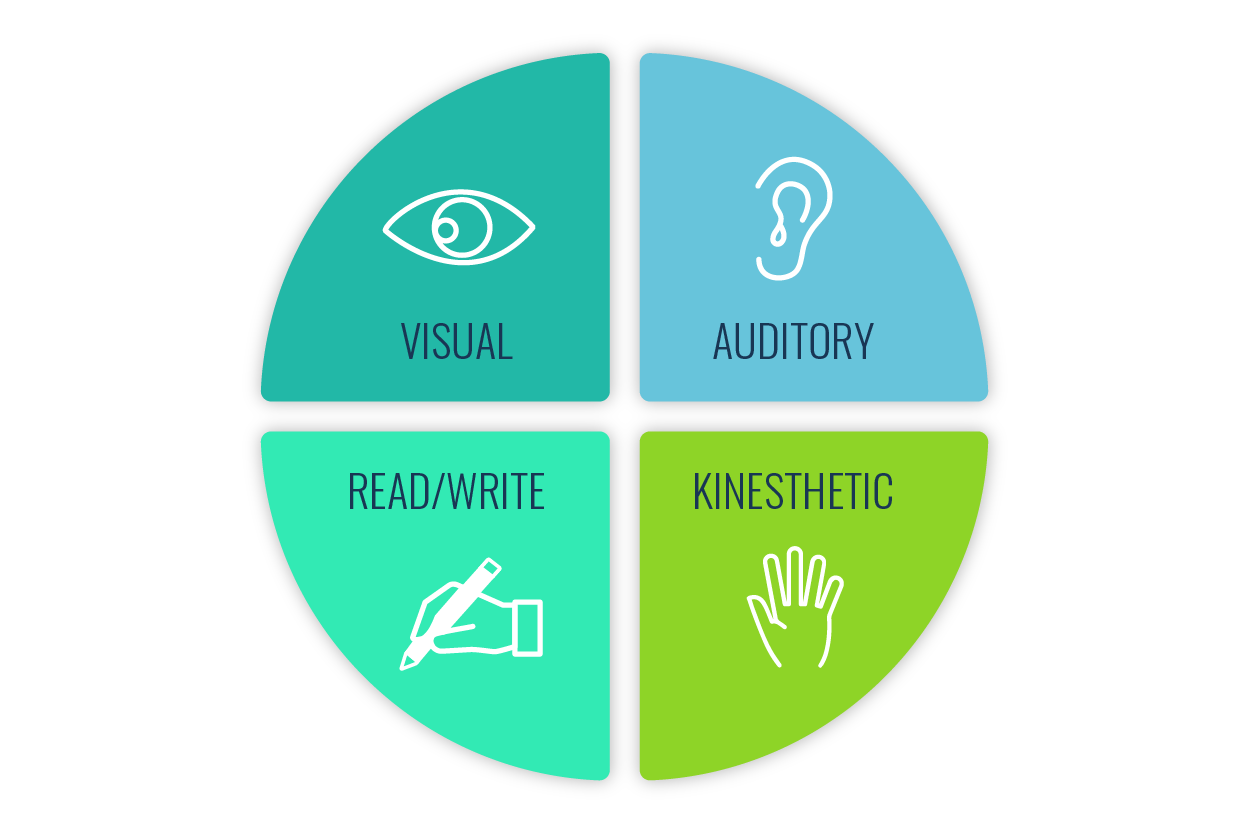

What is the VARK Model?

The VARK model is a theory about learning styles developed by Neil Fleming in 1987. It suggests that learners have preferences for how they take in and process information. Few would argue with that. The controversial part of the theory is the suggestion that catering to these preferences can improve learning outcomes.

Fleming spent 9-years as a senior inspector in the New Zealand school system. During this time, he observed over 8,000 lessons. He noticed that some highly-regarded teachers struggled to connect with students. On the other hand, less-established educators occasionally seemed to have more success.

Naturally enough, Fleming sought to understand these differences. This curiosity fueled his decision to delve deeper into learning styles upon joining the faculty at Lincoln University.

The Origin of The VARK Model

This was not a completely original idea. Educational psychologists were playing with the concept of learning styles back in the 1920s. Honey & Mumford created a learning styles inventory in 1982. David Kolb followed up with another influential model in 1984.

But it was the VAK model, developed by Walter Burke Barbe in the late 1970s that laid the groundwork for Fleming’s approach. This model identified three primary learning modalities: visual, auditory and kinesthetic.

Fleming’s innovation was in splitting the visual dimension (the ‘V’ in VAK) into two parts: visual and read/write. With this, the VARK model was born.

Aiming for a practical tool, Fleming developed the VARK questionnaire, a self-assessment survey for learners to identify their preferred learning style. You can view the current version of the survey here. With that said, let’s dive into the categories themselves.

The VARK Categories

As you may have guessed, VARK is an acronym which stands for visual, auditory, read/write and kinesthetic. For our purposes, we’ll be writing about each learning modality as if they actually exist, before exploring their validity later in this article.

1. Visual Learners (V)

Visual learners excel at processing information they can see and interpret. This means they thrive on charts, diagrams, graphs, pictures, flowcharts and demonstrations. Video is a particularly effective way of getting through to them.

Typically, visual learners have great spatial awareness and can easily remember details from images or illustrations.

They’re good at interpreting visual data and following step-by-step instructions (provided they are accompanied by images).

Lengthy text-based explanations or lectures without visual aids can pose a challenge for visual learners. They may struggle to stay engaged and retain information if they lack the visual stimulation they crave.

2. Auditory Learners (A)

Auditory learners learn best by hearing information presented verbally. They’re the ones who actively participate in class discussions and soak up knowledge through lectures and presentations. They also benefit from group work, podcasts and audiobooks.

Typically, these learners have strong memories for spoken information and excel at following instructions or learning through storytelling. They are often happy to participate in discussions and tend to be good communicators.

Like visual learners, auditory learners are likely to struggle with lengthy written materials. They’ll find it challenging to concentrate in noisy environments, and may choose not to participate in hands-on activities.

3. Read/Write Learners (R)

Read/write learners thrive on information presented in text format. This includes textbooks, articles, written instructions and notes. Fleming introduced this category to capture a separate preference from visual learning.

As you might expect, these learners have excellent reading comprehension and written communication skills. They’re great note-takers and can effectively organise information through their writing.

That said, they may struggle with lectures, presentations and demonstrations that lack clear structure.

To help overcome this challenge, you should consider producing written handouts or follow-up documents.

4. Kinesthetic Learners (K)

This brings us to our last learning style. Kinesthetic learners excel at learning through movement and by getting hands-on. They thrive on activities, experiments, simulations, demonstrations, and role-playing scenarios.

Kinesthetic learners often have excellent hand-eye coordination and spatial awareness.

They’re ‘doers’ and active participants, so tend to retain information best when physical engagement is required.

On the other hand, they may find it difficult to stay focused in environments that require long periods of sitting still. With this in mind, traditional lectures or lengthy written materials are likely to present a real challenge.

Multimodal Learners

Of course, not all learners can be neatly categorised with a single preference. Multimodal learners are those who prefer to use two or more of the VARK modalities. These learners find it easier to switch between modalities, depending on what they are working on.

For instance, if you’re a multimodal learner viewing a lecture, you may be able to both listen effectively (A) and take very good notes (R). As a result, multimodal learners are the most adaptable students and often develop well-rounded cognitive skills.

The VARK Model in Practice

To help you understand these categories better, consider the following analogy. Imagine you’ve been tasked with learning a new recipe. Learners in different categories are likely to approach this task in different ways.

- Visual learners would require clear pictures, diagrams or even a video to follow.

- Auditory learners could be talked through each individual step.

- Read/write learners would read through the instructions carefully.

- Kinesthetic learners would jump right in and get their hands dirty.

- And Multimodal learners would try a combination of different strategies.

The Distribution of Learning Preferences

With over a million learners having completed the VARK questionnaire, it has become a significant source of data on self-reported learning preferences. Let’s delve into the questionnaire results, starting with the distribution of learning style preferences.

- Visual Preference: 1.9%

- Aural Preference: 5.7%

- Read/write Preference: 3.3%

- Kinesthetic Preference: 23.2%

- Multimodal Preference: 66%

The data reveals some interesting trends. Kinesthetic learners appear to be the most common single preference, whilst visual learners are a rare breed. This aligns with the 70:20:10 model, which suggests that the majority of learning happens through experience.

However, the most popular category (by far) seems to be learners with a multimodal preference. Of these multimodal learners, 20.1% have a preference for two styles, 15% have a preference for three styles and 31% have a preference for four styles.

In other words, despite the VARK model’s best attempts, the majority of learners cannot be neatly categorised. Indeed, there are more learners that have a preference for all four styles (31%) than there are those with the most popular single preference (23.2%).

When learners were asked if their learning style matched their own perception of how they learn, 72% said that it did. What’s more, 80% of survey respondents said that they expected VARK to be helpful for their learning.

The Limitations of The VARK Model

As with other learning style models, VARK has some serious limitations. It’s important that you are aware of these considerations, so that you are able to make informed decisions about your learning programme.

- Limited Evidence: Here’s a key point to remember. Learning style models are not research-backed. There is no definitive evidence that matching teaching methods to a learner’s reported style significantly boosts learning. Preferences alone don’t ensure better outcomes.

- Oversimplification: The VARK model categorises learners into four different styles (visual, auditory, read/write and kinesthetic). However, as we’ve seen, most learners have a blend of preferred styles. What’s more, their preference is likely to vary depending on the subject matter they’re tackling.

- Self-Reporting: Self-knowledge is difficult. As a result, we may not always be fully aware of our most effective learning style and how this preference shifts over time. This is an issue, as the VARK questionnaire relies on self-assessment. If we get it wrong, we’re stuck with the results.

- Implementation Challenges: Catering to four distinct learning styles can be resource-intensive and challenging to implement in practice. Whilst the VARK model suggests incorporating diverse teaching methods, it doesn’t provide specific guidance on how to tailor instruction to each style.

- Style Over Substance: Focusing on learning styles sometimes overshadows the importance of effective learning design principles. Research-based strategies like spaced repetition, retrieval practice and self-explanation demonstrably improve outcomes. Focus on what’s proven, rather than what’s popular.

What Does The Research Say?

Unfortunately, there is very little evidence to support learning style models. Indeed, according to the Education Endowment Foundation, the ‘security of the evidence around learning styles is rated as extremely low’. Ouch. Here’s what the studies tells us:

- According to this 2017 study of Malaysian students, there is no meaningful connection between learning styles and academic performance.

- Furthermore, this 2020 study of dental students shows ‘no significant relationship between learning styles and academic achievement’.

- And whilst this 2023 study suggests that learning styles ‘may’ be related to academic performance, it also notes that ‘this relationship is complex and influenced by various factors’.

Despite the lack of supporting research, the VARK model’s popularity among educators is striking. In fact, nearly 90% of instructors believe in learning style models like VARK.

Perhaps this is because the model holds some intuitive appeal. It seems natural enough to suggest that tailoring instruction in line with our preferences is likely to result in higher levels of active engagement and better overall outcomes.

However, having a preference tells us nothing about the quality of any associated acts. We may prefer lounging on the couch to going for a jog, but that doesn’t mean it’s good for us. Likewise, enjoying a detective novel doesn’t guarantee success in real-life detective work.

Similarly, preferring to learn visually (through charts and diagrams) doesn’t guarantee that this method will lead to the best understanding of a complex topic. After all, effective learning often involves exposure to a variety of learning methods.

As Fleming himself puts it: “I sometimes believe that students and teachers invest more belief in VARK than it warrants… You can like something, but be good at it or not good at it… VARK tells you about how you like to communicate. It tells you nothing about the quality of that communication.”

Applications for Learning Professionals

While research on the VARK model’s direct impact on learning outcomes is inconclusive, dismissing the concept of learning styles altogether would be shortsighted. Here’s why you should still take care to understand your learners’ preferences:

- Understanding Metacognition: The VARK model is a valuable tool for sparking discussions about learner preferences. This process of self-reflection (often referred to as metacognition) can help us to identify strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities for improvement.

- Addressing Different Needs: Even if the model doesn’t categorise learners perfectly, it does highlight the importance of using a variety of instructional methods. This can help you to cater to the diverse needs and preferences of your learners. Variety really is the spice of life.

- Driving Engagement: Creating a variety of learning experiences gives your learners more opportunities to engage. This is particularly true if you take care to incorporate compelling visuals, activities, and discussions. Why not gamify each experience as well?

Just remember, while the VARK model can be a useful starting point, you also have other factors to consider. This includes student strengths (beyond their self-reported styles), their prior knowledge and your specific learning objectives.

Effective learning will always hinge on well-designed content, clear explanations and engaging activities, regardless of learning style. Focus on research-supported instructional approaches and success is sure to follow.

Final Words

The concept of learning styles has a complex reputation. Some learning professionals find it an intuitive framework for understanding learner preferences, while others see it as a learning myth that shifts focus away from more effective techniques.

As the most recognisable representative of the learning styles concept, the VARK model sits at the centre of this debate. However, despite its limitations, there’s no doubt that it has sparked valuable discussions about learner preferences.

Whilst you should ultimately focus on evidence-based strategies, understanding these preferences is a useful starting point. Challenging your learners to reflect on their preferences can even improve their metacognitive abilities.

So, the next time somebody declares themselves to be a visual learner, you’ll know the truth of what that means and the limitations that come with it. Now it’s up to you to use this knowledge to guide your learners to unlock their full potential.

Thank you for reading. VARK is just one of many models that learning professionals should be aware of. Get the full breakdown in our bumper guidebook, ‘The Learning Theories & Models You Need to Know‘. Download it now!