The ever-evolving landscape of education continues to be riddled with misconceptions and myths about learning and the way our brains operate. After all, we’re all in search of a quick fix: the ability to learn without actually having to work.

Unfortunately, unlike Keanu in The Matrix, you can’t download karate expertise in a matter of moments. Real learning takes effort. That’s part of the reason why it’s such a rewarding pursuit. If it was easy, we’d all be Einstein-level geniuses.

Raise your hand if you’ve ever believed that your goldfish has better focus than you, or that listening to Mozart makes you smarter. The world of learning is a hotbed for strange beliefs that lack empirical evidence.

So, how much of what you ‘know’ about learning is actually true?

Fear not, fellow knowledge seekers. The Growth Engineering team is here to help you separate fact from fiction. Our goal is not only to dispel misinformation, but also to light the path towards more research-backed learning approaches.

Ready? Then let the myth busting begin!

The Top 12 Learning Myths

We’ve identified 12 of the most common myths about learning, ready to be debunked with evidence-based insights. We’ll also provide practical strategies to replace these misconceptions with empowering learning truths.

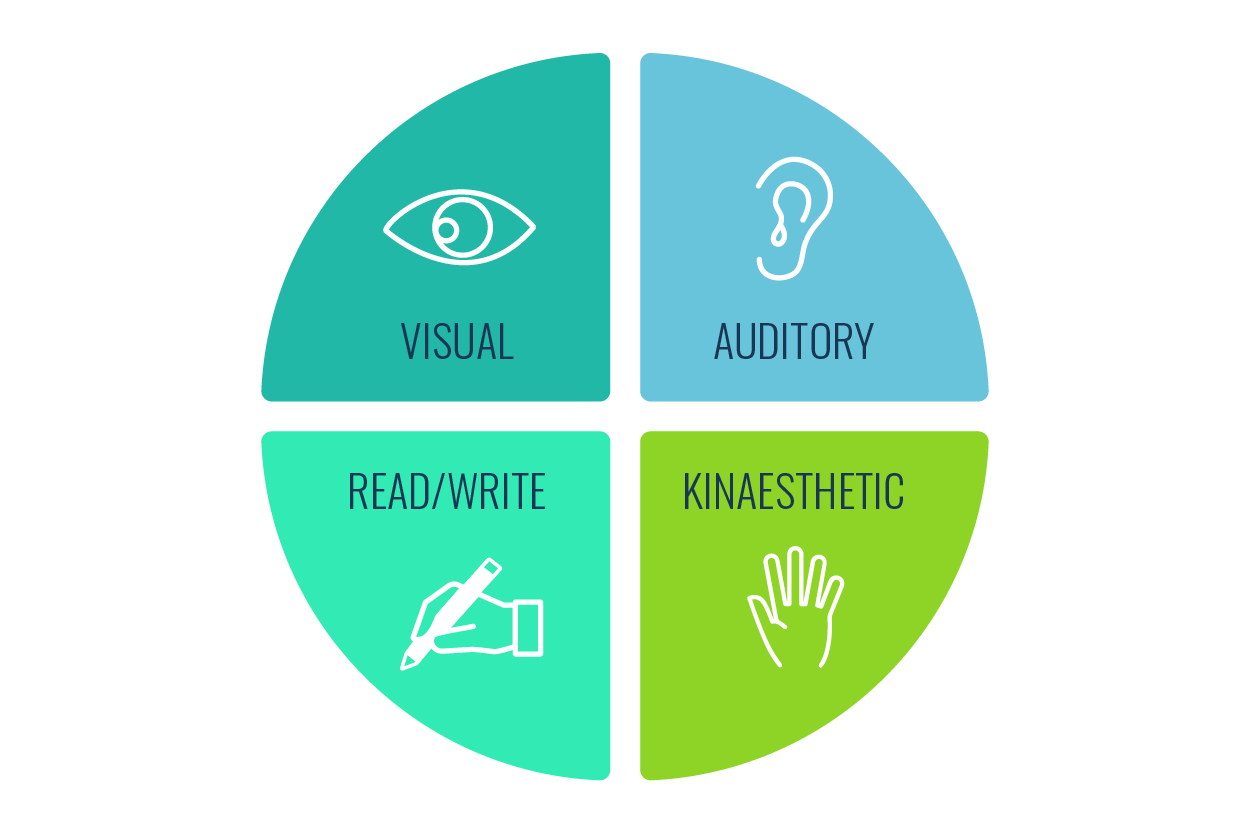

Myth 1: We All Have a ‘Learning Style’

At some stage, you’ve likely heard that people have a dominant learning style (visual, auditory, kinesthetic, etc.) and that we learn best when instruction caters to it. This concept is based on the VARK model, which proposes four distinct learning styles:

- Visual learners: Who supposedly learn best through images, diagrams and demonstrations.

- Auditory learners: Who supposedly learn best by listening to lectures, podcasts or explanations.

- Reading / writing learners: Who supposedly learn best through written text or writing up notes.

- Kinesthetic learners: Who supposedly learn best by doing and getting hands-on whenever possible.

Not the use of the word ‘supposedly’ here. Despite the fact that 90%+ of us believe in learning styles, there is no evidence that they improve learning outcomes. In truth, we use various methods to learn based on the context and complexity of the material.

This belief is also restrictive. Identifying with a single learning style can be a self-fulfilling prophecy that limits exploration and enables you to avoid responsibility for any lack of progress.

The best we can say is that learners might have preferences for certain learning formats, but that these preferences don’t impact outcomes. As such, whilst you should embrace variety, don’t waste time chasing this unicorn.

Myth 2: Multitasking Makes Us More Productive

Ever feel like you’re juggling a million tasks at once? We’ve all been there. Whilst around 2.5% of us are ‘supertaskers’ capable of multitasking effectively, the rest of us perform better by focusing on one task at a time.

The myth here is the misconception that we can effectively perform two or more demanding tasks at the same time, leading to increased productivity. In reality, however, our brains cannot truly multitask.

That’s right. Checking emails during a meeting, or scrolling through TikTok whilst working isn’t effective. When we attempt to multitask, our brains actually rapidly switch attention between tasks. As you might expect, this increases our mental workload and triggers a performance penalty.

As neuropsychologist Cynthia Kubu puts it: ‘The more we multitask, the less we actually accomplish, because we slowly lose our ability to focus enough to learn.’

Instead of multitasking, we’d recommend focusing on becoming a monotasking maestro. This requires expert time management and the ability to minimise distractions and interruptions. Don’t forget to schedule in short breaks to recharge too.

Myth 3: Cramming Works

Ever find yourself staying up late before an exam, rushing to absorb as much information as possible? Whilst this is a common scenario, research suggests that intense last-minute studying (aka. cramming or massed study) isn’t the most effective learning strategy.

Cramming’s allure is clear. It fosters a temporary sense of familiarity with the material, and sometimes it even allows us to recall enough information to pass an exam or test. This can lead to the mistaken belief that it’s an effective learning strategy.

In reality, however, much of this information will never make it into our long-term memories. After all, there’s a wide gulf between memorising something and truly understanding it. The forgetting curve is unforgiving.

Cramming also comes with significant drawbacks, like increased stress and anxiety. To ensure optimal performance, prioritise getting a good night’s sleep before the big day. And whilst you’re at it, why not practise proven learning methods like spaced repetition and active learning?

After all, a University of California study has found that spacing out learning was more effective than cramming for 90% of students.

Myth 4: Left-Brain vs. Right-Brain

Are certain abilities innate and unchangeable? According to the left brain vs right brain myth, our brains are divided into two distinct hemispheres with completely separate functions. As a result:

- Left-brain dominant people are supposedly more logical, analytical and better at subjects like maths and science.

- Right-brain dominant people are supposedly more creative, artistic, and intuitive.

There’s just one problem with this theory: neuroscience actively disproves it. Our brains work as an integrated whole, drawing from both sides for complex tasks. As a result, our abilities and talents are not predetermined in this sense.

This is another limiting belief. You’re not naturally bad at something based on a dominant brain hemisphere. In fact, our brains are highly adaptable. If we apply the right learning strategies then we can improve our skills in a variety of areas.

Hungry for proof? A study by the University of Utah found that ‘both sides of the brain were essentially equal in their activity on average’.

Myth 5: Learning Gets Harder As We Get Older

You can’t teach an old dog new tricks. Or can you? This refers to the misconception that our learning ability significantly declines after a certain age, making it difficult or impossible for older adults to learn new things.

Well, we’ve got good news. Neuroscience research shows us that it’s never too late to learn. Neuroplasticity means that our brains retain the ability to adapt, learn and form new neural connections throughout life.

While some cognitive functions naturally slow as we age, this does not mean learning stops. In fact, research by Scientific American suggests that with the right conditions, older adults can achieve cognitive performances comparable to people decades younger.

As it happens, older brains might be better at meeting some learning challenges than younger ones. After all, the older you get the more experiences you can call upon. This context provides a rich cognitive reserve that enables learners to adapt as they grow.

The key takeaway? Embrace lifelong learning! Whether you’re 20, 40, 60 or 80, stay curious, challenge your mind and keep exploring. After all, your brain has a remarkable capacity to learn and grow throughout life.

Myth 6: Our Attention Span is Smaller Than a Goldfish’s

Ever wonder if humans truly have an attention span shorter than a goldfish’s? Well, 50% of us believe this to be the case, despite this meaning that our focus would only last a few seconds.

However, this comparison is a bit fishy. While a 2015 Microsoft study investigated changes in human attention, it did not claim our attention span is shorter than a goldfish’s. And research largely contradicts this widely held belief.

This is similar to the unfounded suggestion that students can only focus on a lecture for 10 to 15 minutes.

It’s important to understand that human attention is not a singular, fixed entity. In fact, there are several types of attention, such as sustained attention, selective attention, and divided attention, each with its own capabilities and limitations.

The danger here is that we might start to prioritise short-term attention grabs over deeper learning and understanding. Whilst microlearning has its role, we should strive to foster engagement through relevant and stimulating learning experiences and effective communication.

Myth 7: 10,000 Hours of Practice Leads to Mastery

Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers popularised the notion that 10,000-hours of deliberate practice are necessary to achieve mastery in any field. However, this suggestion is an oversimplification of the complex process of skill development.

Indeed, Anders Ericsson calls the 10,000-hour rule ‘a provocative generalisation’.

While the 10,000-hour rule emerged from research on violinists, it’s not universally applicable. As you might imagine, learning and mastery vary significantly across different fields.

This rule also places emphasis on the wrong thing. Not all practice is equal. After all, accumulating hours of mindless practice will get you nowhere. Deliberate practice, on the other hand, focuses on genuine performance improvements, rather than mechanical repetition.

Moreover, research indicates a limited correlation between practice and skill variation. This suggests that other factors significantly influence skill development, such as innate talent, individual motivation, the learning strategies applied and so on.

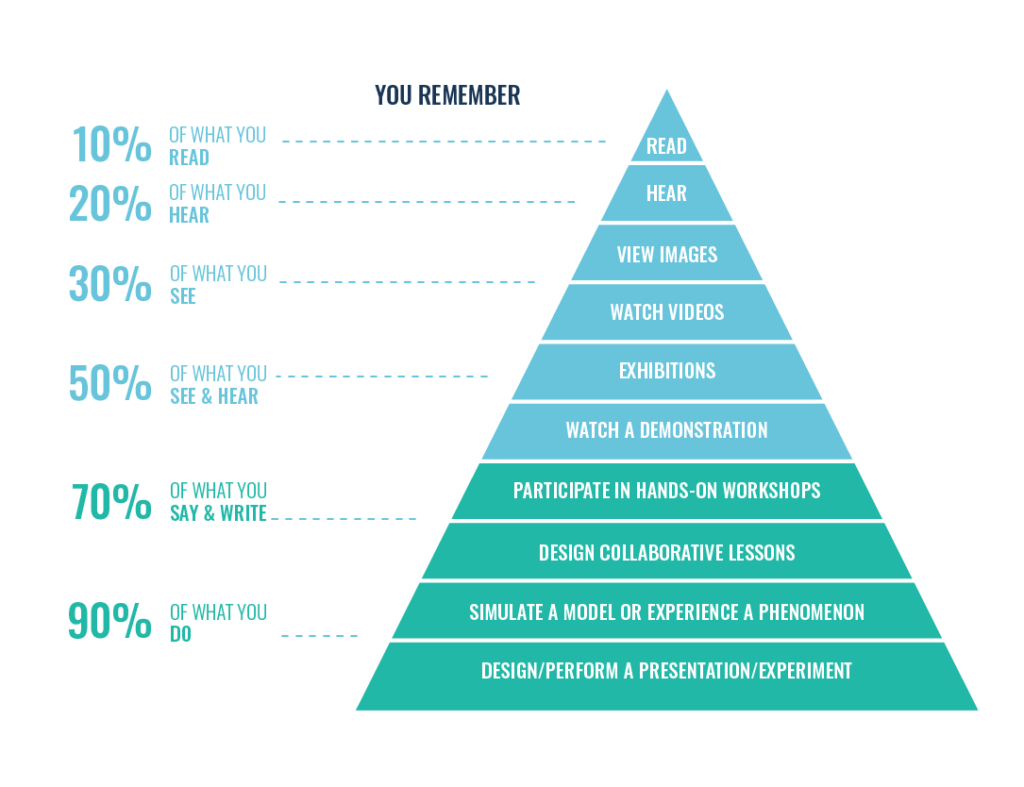

Myth 8: The Learning Pyramid is Accurate

The learning pyramid is a popular, but ultimately unsubstantiated, model that visually categorises the effectiveness of various learning methods. Brazenly, it even assigns specific percentages (with suspiciously round numbers) to each category.

It suggests that we remember:

- 10% of what we read

- 20% of what we hear

- 30% of what we see

- 50% of what we see and hear

- 70% of what we say and write

- 90% of what we do

If only learning were that simple. The learning pyramid appears to be a distorted interpretation of Edgar Dale’s Cone of Experience. Dale’s model categorised learning experiences by their level of ‘concreteness’. Crucially, however, he never included any numerical values or percentages within his concept.

Indeed, these claims lack scientific backing. Research shows that learning effectiveness depends on various factors, not just the method used. As such, we should focus on combining different methods and driving engagement wherever possible.

Myth 9: We Only Use 10% of Our Brains

The myth that we only use 10% of our brain’s capacity resonates with many, perhaps due to the human desire to unlock our full potential. The origin of this myth is thought to be William James’s work on energy reserves in the 1880s.

Movies like Limitless (2011) and Lucy (2014) have taken this concept and run with it. Apparently unleashing 100% of our brains will imbue us with superpowers and psychokinetic abilities.

Of course, the 10% myth is completely debunked by science. fMRI scans show that virtually all brain regions are active during various tasks. Indeed, something as simple as clenching and unclenching your hands requires activity in far more than a tenth of your brain.

As neurologist Barry Gordon puts it, ‘we use virtually every part of the brain, and [most of] the brain is active almost all the time’.

In reality, your brain is a remarkably complex and adaptable organ. While different brain regions have specific functions, they work together to enable learning, thinking, feeling and task completion.

Myth 10: Your Intelligence is ‘Fixed’

The belief that intelligence is fixed from birth is particularly damaging. This misconception suggests that our intellectual capacity is unchangeable. As a result, some people are inherently gifted, whilst others are destined for lower levels of cognitive ability.

Indeed, studies suggest that the belief in fixed intelligence makes people more likely to overestimate their own ability and less likely to develop their own intellectual capabilities. That’s not a great combination.

This belief is also highly discouraging for those who are looking to forge ahead or seize new opportunities by building their knowledge and skills.

Thankfully, intelligence is dynamic and can be affected by various factors throughout your life. This includes environmental factors like education, social experiences, diet, exercise habits and so on.

Cultivating a growth mindset can be incredibly empowering. This approach emphasises the potential for continuous learning and development throughout your life, helping to foster resilience and motivation in the face of challenges.

And don’t forget, intelligence is difficult to define. Indeed, according to psychologist Howard Gardner, we have multiple intelligences, encompassing diverse cognitive strengths and abilities.

Myth 11: All Mistakes Are Bad

What role does failure play in your life? In this section, we’re addressing the misconception that mistakes reflect negatively on one’s intelligence or ability. This belief contradicts the reality that failure is an integral aspect of effective learning.

After all, mistakes provide us with opportunities to identify areas for improvement, reflect on our approach and adjust our strategies for the future. Embracing challenges and overcoming difficulties is what helps us grow.

As Yoda puts it, ‘the greatest teacher, failure is’.

Or, as Scientific American claims, failure has been found to be an ‘essential prerequisite’ for success. Indeed, multiple studies show that failure is a part of long-term sustainable development.

Unfortunately, making mistakes can also damage our self-esteem. This might lead to a fear of trying new things. On the other hand, recognising the valuable insights offered by our mistakes can shift our perspective and encourage us to take on new challenges.

In fact, failure is only really failure if we refuse to learn from it.

Myth 12: Mozart Makes Us Smarter

The Mozart effect is a debunked theory that suggests that listening to Mozart’s music can enhance intelligence, cognitive function and learning abilities.

Wouldn’t that be nice? Perhaps listening to Taylor Swift could also make you kinder, or listening to Beyoncé could make you stronger?

This myth surfaced following a 1993 study by Frances Rauscher. They investigated the short-term effects of listening to Mozart’s Sonata for Two Pianos in D Major on college students’ performance in a spatial reasoning task.

While the initial study observed a temporary improvement in task performance, its limited scope (36 students) and inconsistent replication attempts raise questions about the reliability of these findings.

Besides, who’s to say that it’s Mozart’s music, rather than music in general that’s having a positive impact? After all, research does support the positive effects of music on various aspects of well-being, including mood, relaxation, and stress reduction.

Final Words

The realm of learning is mired with strange and unfounded claims. This highlights our desire for simple explanations and quick solutions. Regrettably, many of these popular beliefs are unhelpful and may even hinder your learning experience.

In reality, learning is a complex and individual process. What works for one person may not be effective for another.

By debunking these myths we can cut through the noise and reach a more enlightened and informed perspective. This empowers us to critically evaluate information, take on new challenges and embrace an evidence-based approach to learning.

And you can achieve all that whether or not Mozart is playing in the background. Pretty liberating, isn’t it?

Ready to transform learning from dull to dynamic? Download our 50+ page guidebook, ‘The Science of Learner Engagement’, for research-backed insights and strategies to boost engagement.