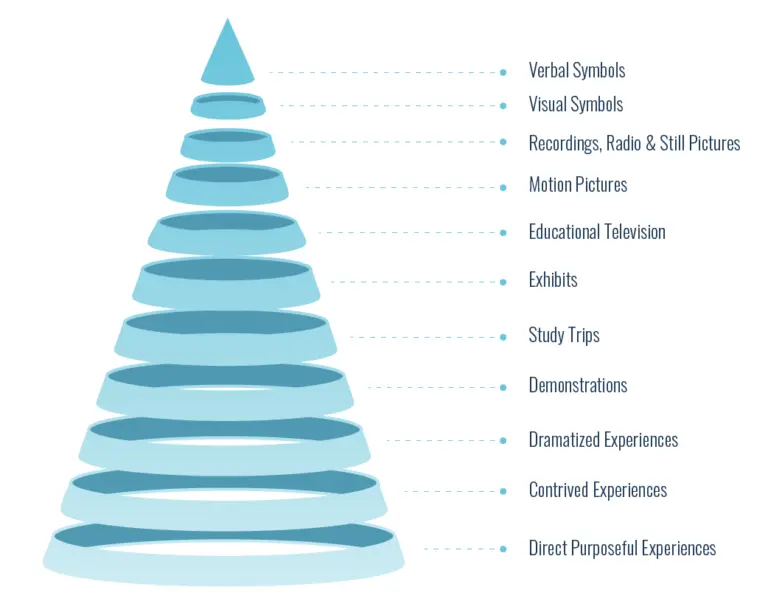

Edgar Dale’s Cone of Experience helps L&D professionals to plan learning experiences that take advantage of the most effective learning environments. This 11-stage model places multimedia elements into categories based on their ‘concreteness’. This is the multimedia asset’s ability to stave off abstractness and capture reality with varying degrees of veracity.

Edgar Dale’s Cone of Experience helps L&D professionals to plan learning experiences that take advantage of the most effective learning environments. This 11-stage model places multimedia elements into categories based on their ‘concreteness’. This is the multimedia asset’s ability to stave off abstractness and capture reality with varying degrees of veracity.

Sounds pretty complicated right? In a nutshell, Dale’s Cone of Experience showcases how we can use a variety of materials and mediums to maximise learner experiences.

Known in some circles as the ‘Learning Pyramid’, Dale’s Cone of Experience is one of the most commonly misrepresented learning theories.

But before we clear up the misconceptions, let’s take a step back and learn more about Edgar Dale, the father of the Cone of Experience.

Who Is Edgar Dale?

Edgar Dale was born in 1900, and he grew up on a family farm in North Dakota, United States. He earned both his Bachelors and Masters degrees from the University of North Dakota and made his way as a teacher in a small rural school.

Dale completed his PhD at the University of Chicago and joined the Eastman Kodak Company. Nowadays simply known as Kodak, the company remains a dominant player in the photography industry.

This can be seen as the start of his research career. After all, Dale completed some of the earliest studies on learning from film while at Eastman Kodak Company.

After this, Dale enjoyed a long career as a professor at Ohio State University (1929-1970). He also served as President of the Division of Visual Instruction of the National Education Association (NEA), now known as the Association for Educational Communication and Technology.

In addition to mentoring doctoral students and working as a professor, Dale made significant contributions in many areas of research. To name a few, his work includes:

- How to Appreciate Motion Pictures (1933)

- Teaching with Motion Pictures (1937)

- Audiovisual Methods in Teaching (1946, 1954, 1969)

- Building a Learning Environment (1972)

- The Living Word Vocabulary: The Words We Know (1976)

- The Educator’s Quotebook (1984)

According to Wagner (1970), Dale used his position to fight relentlessly for a better school system, academic freedom and civil rights.

The Cone of Experience

In his first edition of Audiovisual Methods in Teaching (1946), Dale introduced the ‘Cone of Experience’. The Cone placed different educational media and methods in a continuum from the most concrete experiences at the bottom to the most abstract at the top.

When a learner moves from direct and purposeful experiences to verbal symbols, the degree of abstraction gradually grows. And as a result, learners become spectators rather than participants.

Learners can see, handle, taste, touch, feel and smell the most purposeful experiences. By contrast, verbal symbols, such as use of words, speech or auditory language, at the peak of the Cone are highly abstract. This means they do not have a physical resemblance to the objects or ideas in question.

As such, the Cone of Experience explains the interrelationships of the various types of media and their individual ‘positions’ in the learning process. This makes it a valuable tool that helps instructional designers and L&D professionals incorporate the right audiovisual materials into their classroom or online training interventions.

However, Dale’s Cone of Experience has been widely misrepresented. Let’s have a look at the common misconceptions!

‘Corrupted Cone’ – Common Misconceptions

Dale intended to produce an intuitive model of the concreteness of various kinds of audiovisual media. However, the model has been widely and frequently misunderstood and misused.

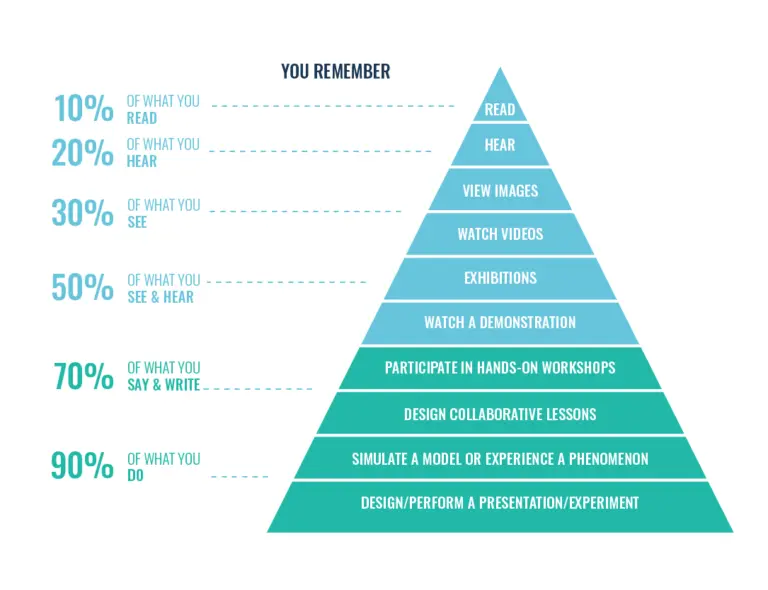

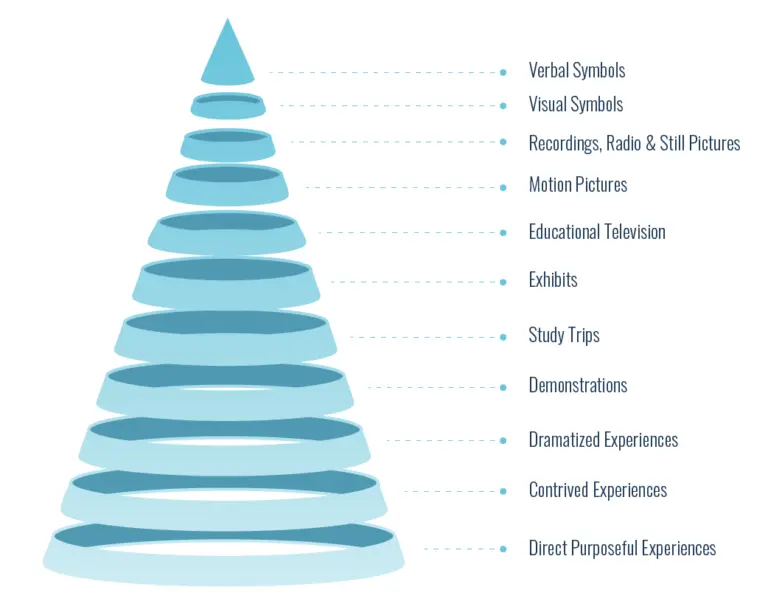

The Cone is often wrongly referred to as the ‘Cone of Learning’, ‘Learning Pyramid’ or ‘Remembering Cone’. What some refer to as the ‘corrupted cone’ is now widely misunderstood as Dale’s Cone of Experience.

Let’s play a game of spot the difference. The illustration directly below is what most share as the ‘Cone of Experience’. You’ve probably seen it before, on social media, or in an article about effective learning approaches.

We’ll come to discover that this cone is completely bogus. It’s the cone below that accurately represents the levels Edgar Dale introduced in his original model. We’ll dig into the detail in the next section.

Mythical Retention Scores

As we can see from the illustrations, the corrupted model purports to inform learners of how much people remember based on how they receive information. According to it, learners generally remember:

- 10% of what they read.

- 20% of what they hear.

- 30% of what they see.

- 50% of what they hear and see.

- 70% of what they say and write.

- And 90% of what do.

Suspiciously round numbers, no? But when you compare the corrupted model to Dale’s actual Cone of Experience, you notice that Dale did not include any numbers or percentages.

In fact, Dale never mentioned the relationship between the level of the Cone and the learners’ level of recall. Instead, he simply used the shape to convey the gradual loss of sensory information in learning interventions.

Still, many educators and learning professionals mistakenly believe that the bogus cone is Dale’s work. And it’s no wonder why! A quick Google search reveals an astonishing number of incorrect attributions.

After seeing how widely the corrupted cone was spreading, Subramony, Molenda, Betrus and Thalheimer combined their powers in an attempt to debunk the myths. They have since published various articles (2014a, 2014b, 2014c) on the topic, and they even have a website focusing on the corrupted cone.

According to their research, the retention data, referring to the percentages seen in the corrupted cone, dates back to ‘folkloric maxims’ from the early 1900s. And while several authors and publications mention such percentages (without the cone), none provide a source for the research.

As such, it doesn’t come as a surprise that these magical retention percentages can be seen to fluctuate significantly. After all, this retention data is not supported by empirical data.

Misunderstood Application

On top of these mystical retention percentages, Dale’s Cone of Experience has been misapplied for decades. For instance, some interpret the model as suggesting that direct learning experiences are inherently better than the more abstract audiovisual experiences offered at the top of the cone.

But this is far from how Dale intended his Cone to be used. In his 1969 edition of Audiovisual Methods in Teaching, Dale notes that the Cone is merely a visual analogy. It shows the progression of learning experiences from the concrete to the abstract.

The shape had nothing to do with deciding that one kind of experience is better than another. It is not a hierarchy of learning efficiency. In fact, Dale even explained that too much reliance on concrete experience may actually obstruct the process of meaningful generalisation.

And on top of all that, Dale actually advised his readers not to take the cone too literally in the first place! He intended the Cone to be a descriptive model, instead of a roadmap for lesson or training planning.

The Cone Uncorrupted

Now that we have overcome some of the misconceptions, let’s have a look at the eleven levels of Dale’s authentic Cone of Experience.

The base of the model is characterised by more concrete experiences. These include direct experiences, contrived experiences and dramatic participation.

The middle of the Cone is slightly more abstract, where learners observe without action. These experiences are less concrete than the lower levels, as learners do not interact directly with the phenomenon.

The peak of the Cone displays the most abstract experiences, which are represented with limited degrees of realism by symbols. These include visual and verbal symbols, like listening to the spoken word.

As such, the arrangement of the levels in the Cone is not based on its difficulty. Instead, it focuses on abstraction and the number of senses involved. Instructional designers can mix and interrelate these experiences to foster more meaningful learning.

Let’s have a look at each level individually, working our way down the Cone!

11. Verbal Symbols

As explored, each level of the Cone moves the learner a step further away from real-life experiences. As such, experiences focusing only on the use of verbal symbols are the furthest removed from real life.

Verbal symbols are highly abstract as they bear no physical resemblance to the objects or ideas they stand for. In fact, these verbal symbols provide no visual representation or clues to their meaning.

Dale used the word ‘horse’ to illustrate this. Writing the word ‘horse’ does not look like a horse, sound like a horse or feel like a horse. In fact, the letters H-O-R-S-E don’t look, sound, smell, taste, or feel anything like the actual animal.

This is true, regardless of the language you use. For instance, you spell a horse as ‘hevonen’ in Finnish, ‘cheval’ in French or ‘hest’ in Danish. Fun words, no doubt, but none of them resemble the animal itself. Instead, they share a common meaning that native speakers often learn at a very young age.

10. Visual Symbols

The other highly abstract level includes visual symbols, such as charts, maps, graphs and diagrams that are used for conceptual representation. These visual symbols help to make just about any reality into something easier to understand.

In fact, from sports team logos to traffic signs, we see symbols everywhere. These symbols help people understand the world. Just as with verbal symbols, visual symbols help drive understanding by conveying a meaning that is shared by the rest of society.

Visual symbols often include simple illustrations that do not include any unnecessary detail. This makes them relatively easy to procure and prepare. And that’s what every instructional designer wants to hear, right?

9. Recordings, Radio and Still Pictures

Edgar Dale first created this model in 1946. As such, he included the multimedia assets of his time, such as recordings, radio and still pictures. In more modern terms, this level could include photos, podcasts or audio files.

If you go back to the ‘corrupted cone’, one of the common misrepresentations treats ‘seeing’ as more effective than ‘hearing’.

Yet, Dale placed visual and auditory media on a similar level of abstraction. After all, in both cases, you are merely observing visual symbols (like still photos) or verbal symbols (like audio recordings). Neither example actively asks anything of the learner.

8. Motion Pictures and 7. Educational Television

Most recent publications combine levels eight and seven into one category. After all, motion pictures and television are similar mediums. They enable learners to process real-life processes or events through on-screen recordings.

Motion pictures and educational television include, for example, videos, animations and tv programmes, which imply value and messages through moving pictures. These are abstract experiences, as learners focus on observation instead of active participation.

As a result, learners have little or no opportunity to participate in or use senses other than seeing and hearing. But while streaming experiences can’t recreate the richness of reality, videos do present an on-screen abstraction of real-life processes and events.

In fact, videos are effective for presenting movement and continuity of ideas. You could even say that motion pictures and television provide a ‘window to the world’.

This has benefits when it comes to using videos in training. After all, you can edit out any irrelevant parts, zoom in on details, highlight information, or slow things down to provide focus. Learners can also rewind and replay the video as many times as they need to.

However, there is much controversy surrounding the benefits and disadvantages of television and motion pictures. Yet, research shows that educational programmes can enhance children’s intellectual development and provide experiences that are otherwise unreachable.

6. Exhibits

The sixth level of Dale’s Cone of Experience moves us away from the most abstract experiences. This is the first level that opens the door for an expanded range of sensory and participatory experiences.

In fact, this level can be summarised as meaningful displays with limited handling. After all, most exhibits are experiences that are for the eyes only. Yet, some exhibits include sensory elements that can be related to direct purposeful experiences. These exhibits are specifically designed for interactivity.

As a result, this experience allows learners to see the meaning and relevance of things based on the different pictures and representations presented. Visiting exhibits in educational outlets like museums are a common way to provide learning opportunities.

After all, exhibits are a great way to present students with exposure to new ideas, discoveries and inventions that would be more difficult to display in a classroom setting.

5. Study Trips

Study trips offer the sights and sounds of real-world settings. The main activity focuses on observing from the sidelines, aside from occasional opportunities to participate. Participation could include, for instance, hopping in a fire truck or milking a cow.

These rich experiences help learners to learn more about different objects, systems and situations. As such, study trips provide an opportunity to experience something that learners cannot be encounter within the traditional classroom space.

Similarly, field trips expand the social learning opportunities provided by online learning. As a result, the learning experience is not limited to the traditional training setting but rather extended to a more complex environment.

The effectiveness of field trips has been researched extensively. They are well regarded, given how easy it is to provide every student with the same real-life experience.

In addition, students can see connections between their training experiences and the ‘real world’. This type of elaboration is known to be an effective learning technique.

4. Demonstrations

A demonstration is a visualised explanation of facts, ideas or processes. They are a common way to train employees or students, as they require relatively little preparation and resources. After all, individuals observe a lot simply by watching others.

On top of that, demonstrations can include pictures, drawings, film and other types of media in order to facilitate clear and effective learning. This approach helps to showcase how individuals can complete these tasks in real life.

Like exhibits and field trips, demonstrations may or may not include an element of participation. As such, demonstrations sit in the middle of the Cone based on their abstraction.

Demonstrations are especially useful if a hands-on activity is logistically unfeasible. However, demonstrations don’t come without limitations! Learners may not interpret or conceive the information as well as intended. Other factors affect the learning experience too. For instance, some learners may have worse visibility of the demonstration.

Similarly, demonstrations alone may not be enough in all learning situations. After all, seeing how a task is done is rarely as good as trying to do it ourselves.

3. Dramatised Experiences

Dramatised experiences can be seen as role-play exercises. This means reconstructing situations for learning purposes. As a result, the third level involves shifting learners — at least some of them — from observers to active participants.

This enables learners to participate in reconstructed experiences that could give them a better understanding of the idea or concept. In this manner, dramatising real-life experiences can help learners to get closer to certain realities that are not easily available first-hand.

They also provide a safe environment for experimentation. For instance, it’s much better to fail in a sales negotiation role-play than it is to fail in real life.

Learners can become more familiar with the concepts as they emerge themselves into the “as-if” situation. Similarly, learners can observe their peers to take their learning even further! This enables them to compare and contrast what they may have done differently.

2. Contrived Experiences

The second level is called contrived experiences, which focuses on the ‘editing’ of reality. At this level, teachers use representative models and mock-ups to provide an experience that is as close to reality as possible.

This can make the concept easier to grasp. After all, some realities are far too complex to take in all at once. As such, contrived experiences are imitations that sometimes teach better than the realities they imitate.

Contrived experiences are very practical and make the learning experience more accessible. After all, they have a concrete nature that permits easy visualization and helps to foster a better understanding of the concept at hand. And on top of all that, contrived experiences are easier to manipulate or operate!

1. Direct Purposeful Experiences

The bottom level of Dale’s Cone of Experience is also the least abstract. Direct purposeful experiences are hands-on activities that grant us responsibility for driving a specific outcome. We are active agents in the learning experience. In a sense, direct purposeful experiences are an unabridged version of life itself.

These rich, full-bodied experiences can be considered the bedrock of all education. After all, learners can see, handle, taste, feel, touch and smell these experiences. As such, at this level, learners use more senses in order to build up their knowledge.

Learners learn by doing tasks themselves. As a result, learning happens through actual hands-on experiences.

The Relevance of Cone of Experience

The Cone of Experience was first created decades ago, in 1946. And even decades after his passing, Dale’s work continues to influence the educational technologies field. Its utility in selecting instructional resources and activities is just as practical today as when Dale created the Cone.

The Cone has also inspired the birth of other models. For instance, Baukal et al. (2013) built upon Dale’s ideas and created the Multimedia Cone of Abstraction.

Even though Dale himself recommended not to take the model too seriously, it does guide us in creating effective learning environments. Let’s take a look!

The Cone in Learning And Development

In his 1969 version of Audiovisual Methods in Teaching, Dale introduced ‘rich experiences’. According to Dale, effective learning environments should offer memorable and rich experiences where learners can use multiple senses. He characterised rich experiences as follow:

- Students use their eyes, ears, noses, mouths and hands to explore and immerse the experience.

- Learners have the chance to discover new experiences.

- Training events are emotionally rewarding and will motivate participants to continue learning throughout their lives.

- Students have the opportunity to reflect on their past experiences to create new experiences.

- Learners get a sense of personal achievement.

- And students can create their own dynamic experiences.

As such, it is clear that no one level of Dale’s Cone of Experience is sufficient to generate a ‘rich’ learning experience. With this in mind, instructional designers should focus on creating memorable learning experiences where learners can see, hear, taste, touch and try.

Furthermore, we need to take advantage of other media. As long as all mediums are beneficial for your learners, you can combine as many as you wish.

Learning Strategies

Dale thought that the school system forced students to memorise information instead of actually learning how to think or solve real problems. Unfortunately, the current school system has been criticised for adopting the same approach.

For this reason, Dale argued that we should use revolutionary approaches to improve the quality of educational learning environments. One way to do this is to introduce a range of audiovisual materials to create vivid and memorable learning experiences. Like Dale (1969, p. 23) describes:

“Thus, through the skillful use of radio, audio recording, television, video recording, painting, line drawing, motion picture, photograph, model, exhibit, poster, we can bring the world to the classroom. We can make the past come alive either by reconstructing it or by using records of the past.”

In other words, instructional designers must implement learning strategies fuelled by interaction. They can do so by introducing modern learning techniques.

In fact, a growing body of research shows that training interventions that use well-designed multimedia content are more effective than those that don’t. Text only learning interventions could soon be a thing of the past.

Indeed, to get the best results, instructional designers should mix approaches, balancing concrete and abstract experiences. This helps them to cater to and address all learner needs in order to help each learner in their learning journey.

Modern Learning Technology

Luckily, current learning technology makes this easier than ever before! Growth Engineering LMS, for instance, lets you use a variety of content types to build your training plan. This empowers you to create rich experiences.

This can range from your regular PDFs and slideshows to video and audio files, not to forget virtual classroom sessions and informal learning opportunities. In fact, innovative social learning features ensure learners can discover and create their own dynamic experiences.

Gamification, on the other hand, helps learners to get a sense of personal achievement as they accrue Experience Points (XP) or climb up the Leaderboard. Gamification is also utilised for the most immersive learning strategies, whereby learners physically participate in their training content. This resembles real-life situations and processes.

In addition, some of our modern forms of multimedia were not available when Dale created his Cone of Experience. For instance, virtual reality and augmented reality are relatively new additions to training. These inventions have the potential to showcase extremely realistic simulations that help to create contrived learning experiences.

Similarly, some of the elements in Dale’s Cone, like educational television, are not as relevant today as they were when Dale first created his model. But according to recent research, one could easily update the Cone to tally harmoniously with modern technology.

However, while these assets and approaches help you to create rich training experiences, it’s essential to get the balance right. As such, you should vary your content formats and broader concepts to facilitate effective and meaningful learning.

Final Words

Dale’s Cone of Experience is a wildly misunderstood model. Despite this, it remains useful even for today’s weathered instructional designers.

After all, it showcases how we can use a variety of materials and mediums to maximise learner experiences. It also helps us to think about the sensory impact of our learning content.

Still, if you only take away one thing from this article, let it be this: don’t go around telling people that you only remember 10% of what you read!

If you would like to learn more about different learning models and theories, check out our guidebook ‘Using Learning Theories & Models to Improve Your Training Initiatives’ now!